The gentle "ladies" of Boston, staged a "Coffee Party" in 1777, reminiscent of the earlier Boston Tea Party of 1773. The town's women confronted a profiteering hoarder of foodstuffs confiscating some of his stock of coffee, according to a letter from Abigail Adams to her husband, who would become the 2nd president of the United States.

Abigail Adams by Benjamin Blythe, 1766.

Abigail Adams by Benjamin Blythe, 1766.Writing from Boston, on July 31, 1777, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, away attending the Continental Congress in Philadelphia,

"There is a great scarcity of sugar and coffee, articles which the female part of the state is very loath to give up, especially whilst they consider the great scarcity occasioned by the merchants having secreted a large quantity. It is rumored that an eminent stingy merchant, who is a bachelor, had a hogshead of coffee in his store, which he refused to sell under 6 shillings per pound.

"A number of females—some say a hundred, some say more—assembled with a cart and trunk, marched down to the warehouse, and demanded the keys.

"Upon his finding no quarter, he delivered the keys, and they then opened the warehouse, hoisted out the coffee themselves, put it into a trunk, and drove off. A large concourse of men stood amazed, silent spectators of the whole transaction."

Coffee had been popular in Boston for over a century, when the Revolutionary women of the town became patriotically incensed. Dorothy Jones had been issued a license to sell coffee in Boston in 1670. “Mrs. Dorothy Jones, the wife of Mr. Morgan Jones, is approved of to keepe a house of publique Entertainment for the selling of Coffee & Chochaletto.” The last renewal of Mrs. Jones's license was in April 1674, at which time she was accorded the additional privilege of selling ''cider & wine." Morgan Jones was a minister & schoolmaster who moved from colony to colony frequently, leaving Dorothy Jones to make her own way financially.

17th-century London Coffee House

17th-century London Coffee HouseOne of the earliest references to coffee in the American colonies was in 1668, when a beverage made from the roasted beans flavored with sugar or honey, and cinnamon, was being drunk in New York, usually at breakfast. Soon after the introduction of the coffee drink into the New England, New York, Maryland, & Pennsylvania colonies, trading began in the raw product. William Penn noted buying his green coffee supplies in the New York market in 1683, paying for them at the rate of 18 shillings & nine pence per pound.

1674 London Coffee House

1674 London Coffee HouseSoon coffee houses patterned after English & Continental prototypes were established in the colonies, quickly becoming centers of social, political & business interactions. Among the earlist were London Coffee House in Boston, in 1689; the King's Arms in New York in 1696; and Ye Coffee House in Philadelphia in 1700.

After the Welsh gentlewoman Dorothy Jones opened her 1670 Boston coffee & chocolate establishment, the next colonial coffee house may have been in Maryland. In St. Mary's City, Maryland, the 1698 will of Garrett Van Sweringen, bequeaths to his son, Joseph, "ye Council Rooms and Coffee House and land thereto belonging," which Van Sweringen had opened in 1677.

Coffee Houses in Early Boston

The name coffee house did not come into use in New England, until late in the 17th century. The London Coffee House and the Gutteridge Coffee House were among the first opened in Boston. The latter stood on the north side of State Street, between Exchange and Washington Streets, and was named after Robert Gutteridge, who took out an innkeeper's license in 1691. Twenty-seven years later, his widow, Mary Gutteridge, petitioned the town for a renewal of her late husband's permit to keep a public coffee house.

Boston's British Coffee House, whose named changed to the American Coffee House during the pre-Revolutionary period, also appeared about the time Gutteridge took out his license. It stood on the site that is now 66 State Street, and became one of the most widely known coffee houses in colonial New England.

The Crown Coffee House opened in 1711 and burned down in 1780. There were inns and taverns in existence in Boston long before coffee & coffee houses. Many of these taverns added coffee for patrons who did not care for the stronger spirits.

In the last quarter of the 17th century, quite a number of taverns and inns sprang up in Boston. Among the most notable were the King's Head (1691), at the corner of Fleet and North Streets; the Indian Queen (1673), on a passageway leading from Washington Street to Hawley Street; the Sun (1690-1902), in Faneuil Hall Square; and the Green Dragon, which became one of the most celebrated coffee house & taverns, serving ale, beer, coffee, tea, and more ardent spirits. In the colonies, there was not always a clear distinction between a coffee house and a tavern.

Boston's Green Dragon

Boston's Green DragonThe Green Dragon, stood on Union Street, in the heart of the town's business center, for 135 years, from 1697 to 1832, and figured in practically all important local and national events during its long career. In the words of Daniel Webster (1782-1852), this famous coffee-house tavern was the "headquarters of the Revolution." John Adams, James Otis, and Paul Revere met there to discuss securing freedom for the American colonies. The old tavern was a two-storied brick structure with a sharply pitched roof. Over its entrance hung a sign bearing the figure of a green dragon.

The Bunch of Grapes, that Francis Holmes presided over as early as 1712, was another hot-bed of politicians. This coffee house became the center of a rowsing celebration in 1776, when a delegate from Philadelphia read the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of the inn to the crowd assembled below. In the excitement that followed, the inn was nearly destroyed, when one celebrant built a bonfire too close to its walls.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the title of coffee house was applied to a number of new establishments in Boston. One of these was the Crown, which was opened in the "first house on Long Wharf" in 1711 by Jonathan Belcher, who later became governor of Massachusetts, and then New Jersey. The first landlord of the Crown was Thomas Selby, who also used it as an auction room. The Crown stood until 1780, when it was destroyed in a fire that swept the Long Wharf.

Another early Boston coffee house on State Street was the Royal Exchange. It occupied a two-story building, and was kept in 1711, by Benjamin Johns. This coffee house became the starting place for stage coaches running between Boston and New York, in 1772. In the Columbian Centinel of January 1, 1800, appeared an advertisement in which it was said: "New York and Providence Mail Stage leaves Major Hatches' Royal Exchange Coffee House in State Street every morning at 8 o'clock."

In the latter half of the 18th century, the North-End coffee house in a 3 storey 1740 brick mansion, stood on the west side of North Street, between Sun Court and Fleet Street. One contemporary noted that it had forty-five windows and was valued at $4,500. During the Revolution, it featured "dinners and suppers—small and retired rooms for small company—oyster suppers in the nicest manner."

Boston coffee-houses reached the height of popularity in 1808, when the doors of the Exchange Coffee House were thrown open after 3 years of building. It was the most ambitious coffee-house project the new nation would know. Built of stone, marble, and brick, it stood seven stories high, and cost a half-million dollars. Charles Bulfinch, one of America's most noted architects of that period, was the designer.

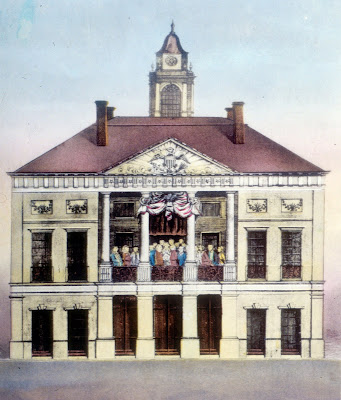

Boston's Exchange Coffee House from History of Boston published in 1828

Boston's Exchange Coffee House from History of Boston published in 1828It was patterned after Lloyd's of London, and was the center of marine intelligence in Boston, and its public rooms were thronged all day and evening with mariners, naval officers, ship and insurance brokers, who had come to talk shop or to consult the records of ship arrivals and departures, manifests, charters, and other marine papers.

The first floor of the Exchange was devoted to trading. On the next floor was the large dining room, where many banquets were given, notably one honoring President Monroe in July, 1817, which was attended by former President John Adams, and many generals, commodores, governors, and judges. The other floors offered sleeping rooms, of which there were more than 200.

The Exchange Coffee House was destroyed by fire in 1818; and on its site was erected another, bearing the same name but having slight resemblance to its predecessor.

The War of 1812 put a temporary damper on the popularity of coffee. When the cost of the War of 1812 made necessary more revenue, imports of coffee were taxed ten cents a pound. A war-time fever of speculation in tea and coffee followed, and by 1814 prices to the consumer had advanced to such an extent (coffee was 45 cents a pound) that the citizens of Philadelphia formed a non-consumption association, each member pledging himself "not to pay more than 25 cents a pound for coffee and not to consume tea that wasn't already in the country."

The war was just a temporary blip in the popularity of coffee in America. Per-capita consumption grew to 3 pounds a year in 1830, 5 1/2 pounds by 1850, and 8 pounds by 1859. By the 1870s, coffee had become an indispensable beverage for Americans, who consumed 6 times as much as most Europeans.

.